Introduction: The Stellinga Revolt

The year 840 was a tumultuous year for the Carolingian Empire. Since the late 700s, the empire had dominated Western Europe, with Charlemagne and his heirs conquering pagan peoples and enforcing Christian feudal laws. The policy of the empire primarily derived from a doctrine of restoring the old Western Roman Empire, which had fallen to the Barbarian Kingdoms years before.

However, these Frankish institutions kept to Roman tradition a little too well with a raging civil war. Louis the Pious had died and left a realm divided between his three sons Lothair, Louis the German, and Charles the Bald. These three wasted no time squabbling about who would be the true emperor and rule the most territory, which was, by all means, a simple and typical feudal war based on the region’s expectations. But then, sudden as lightning, up from below came a peasant rebellion unlike any seen for centuries.

Gerward, a Frankish author who composed the Annales Xantenses, described the uprising as follows: “Throughout all of Saxony the power of the slaves rose up violently against their lords… they usurped for themselves the name Stellinga and the nobles of that land were violently persecuted and humiliated by the slaves.”

The word Stellinga comes from Old Saxon and means “the companions” or, somewhat humorous for some folks, “the comrades.” These men were of the social classes known as frilingi and lazzi by the feudal law of their day, best expressed in our understanding as freemen and freedmen, and their demands were simple. They wanted a restoration of the social and political rights guaranteed to them under the order of the Saxon Confederation of tribes which held sway before Charlemagne conquered, converted, and enforced his order upon them.

The Saxon Confederation: Governance Before The Carolingian Empire

But what were these rights? Simply put, everything. The Saxon Confederation had a very decentralized government. Anglo-Saxon writers such as the Venerable Bede in England characterized the region as somewhat lawless, quoting from Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, “For those Old Saxons have no king, but many ealdormen set over their nation; and when any war is on the point of breaking out, they cast lots indifferently, and on whomever the lot falls, him they all follow and obey during the time of war; but as soon as the war is ended, all those ealdormen are again equal in power.”

This description broadly matches what we know about general Germanic law and governance practices, wherein communities generally govern themselves via Things or assemblies, where any free member of society can make their voice heard in deliberation and have an equal vote in all matters of importance. A significantly earlier form of this government, though one that was likely incredibly similar in practice, was recorded by Tacitus in his Germania as follows.

“On matters of minor importance only the leading men debate, on major affairs the whole community; yet even where the commons have the decision, the matter is considered in advance by the leaders… When the crowd so decides, they take their seats fully armed. Silence is then demanded by the priests, who on that occasion also have the right to enforce obedience. Then such hearing is given to the king or leading man as age, rank, military distinction or eloquence can secure; it is their prestige as councilors more than their power to command that counts. If a proposal displeases them, the people roar out their dissent; if they approve, they clash their spears.” – Tacitus, Germania

Similar systems can be seen across the historical Germanic world as a form of somewhat anarchist governance and can even still be seen today in some parts of Switzerland under the name Landsgemeind.

Under this form of Thing government, the Saxons would’ve had a right to involvement on any level of the political system, they would have the right to freedom of movement and freedom of association, and they would not have been bound by law to a feudal hierarchy, only serving under those leaders who they saw fit to swear themselves to. Furthermore, other rights were denied to them by Charlemagne in a code of laws he specifically created for the Saxons after having conquered them.

These laws, on pain of death, forbade the Saxons to engage in religious and cultural ceremonies such as cremation burial, the creation of idols, the celebration of a number of ceremonies, and even to refuse the rite of baptism for themselves and their children. These rights to freedom of association, political autonomy, and religious liberty were what the Stellinga were fighting for.

In fact, religious autonomy seems to have been an indispensable part of the movement. Earlier Saxon rebellions against the Carolingians, such as those led by Widukind, were primarily spurred by the destruction of Heathen temples and forced baptisms. One of the factors that may have made Widukind so influential could’ve been some religious standing. However, we cannot be sure about that element.

Two of our primary sources on the activities of the Stellinga, Nithard, and Prudentius of Troyes both emphasize the degree to which the uprising was vehemently anti-Christian, burning churches and engaging in Heathen rituals. Though this may not have been universal, other sources lack this information and the most likely situation is that many of the Stellinga were Heathens, many were Christians, many were syncretic, and all of them wanted equal rights and the freedom to do whichever religious rituals they pleased as their ancestors had before the days of Charlemagne.

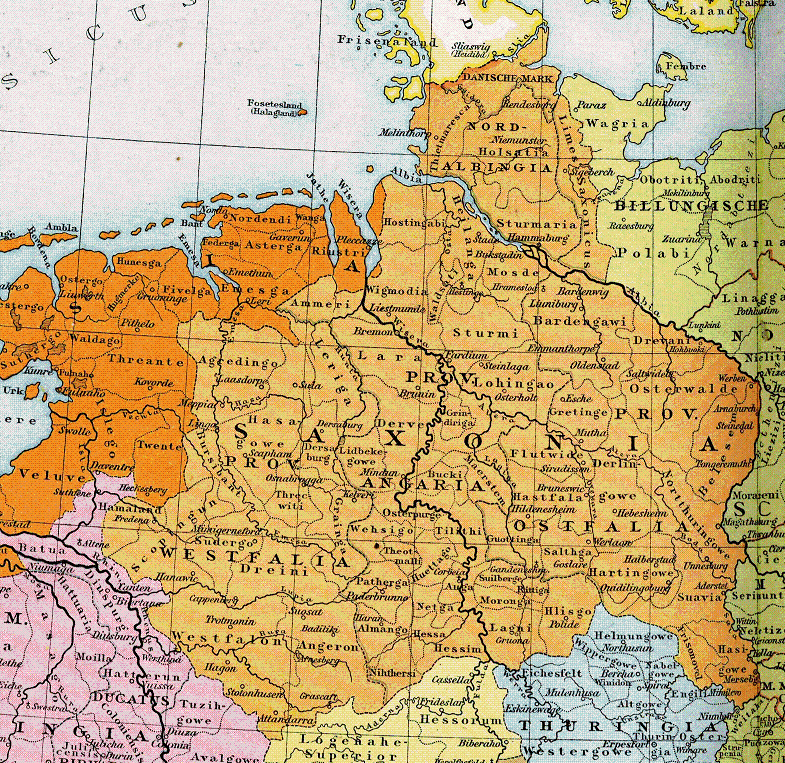

Guerrilla Warfare in Northern Germany

Not much is reliably recorded about the on the ground action of the uprising itself. What seems to be the case is that it was able to swiftly and effectively gain control of large swathes of territory in what is now Northern Germany, likely due to the common feeling of discontent held by Saxons with their current government. The forces likely also benefited from their ability to stay agile, hostile, and mobile, as Saxon warfare against the Carolingians had historically seen the most success when attack forces of common people struck in ambush style guerilla campaigns that the large organized Frankish armies were ill equipped to fight back against.

This same song and dance was seen before both in the Germanic campaigns in Teutoburg Forest and the Gallic resistance to Caesar, proving the long history of its efficacy in Germanic and Celtic warfare both between themselves and against their imperialist enemies. The so-called “ringleaders” of the movement also likely stayed on the move in order to avoid capture and to best be able to coordinate strikes in the field.

Leadership of the movement was likely determined on a local communal level, and many medievalists believe the most accurate way to view the Stellinga as a whole is the interconnected uprising of multiple small and self-governing communities who shared common laws, common methods of organization, and common goals. Simply put, the Stellinga was a smaller scale rebirth and reemergence of the Saxon Confederacy itself through community organization and mutual aid. These methods and early victories made them immediately stick out to the Carolingian elites.

Christianization: The Betrayal and Fall of the Stellinga

However, as so often unfortunately happens to rebellions of the common people, the cause of the Stellinga was hijacked by an authoritarian, imperialist, colonialist force. When the Carolingians took control of Saxony, they instituted a local order of feudal nobility from among the converted Saxons, as was their policy, one eerily reminiscent of Rome’s earlier policy towards certain conquered Barbarians. A local governing class loyal to the emperor, converted to the new faith and beliefs, “civilized” to satisfaction, and still able to engage just enough with the local culture to keep dissent low.

In a remarkable example of how this civilizing policy towards the Barbarian was effective, one of these noble families, the Liudolfingers, later founded the Ottonian Dynasty and the Holy Roman Empire. As always in these early stages, Christianization and the goals of Romanization greatly resemble forms of whiteness and racialization. In the Carolingian Civil War, these Saxon nobles were firmly aligned with Louis the German.

In response to this and the rise of the Stellinga, a force increasingly to be reckoned with, Louis’ rival Lothaire took up an opportunity for easy and expansive support in the region. At a meeting at Speyer in the year 841, he readily promised the Stellinga that if only they would support him in his claim on the throne, he would bestow upon them all of the rights and freedoms they desired. The Stellinga agreed and resumed fighting their enemies in the region, slowly being whittled down by the whims of warfare.

Not long after this meeting, the unnamed leaders of the movement, having exposed their positions, Louis the German captured and killed them. This left the movement largely fractured and divided, and by the year 843 the Saxon nobility under Louis had regained control and subjected the once free Saxons again to the indignity of feudal peasantry.

For more on Romanization see: The Detribalization of Europe

Legacy

Another such uprising would not occur for over a hundred years, led by a Slavic people facing a similar position to the Saxons as the insatiable hunger of the Christian kingdoms led them into the Ostleidung. The heritage of the Stellinga remained strong in the region for some time afterward. Materialist historians in East Germany spent pages upon pages debating it and its implications for the history of the German working class effort. While that is an excellent takeaway and one that I encourage bringing forward into modern discourse, many other elements must be considered.

The Stellinga is an almost ideal example of an occupied people of Europe attempting to achieve a very similar goal to those of us here at Touta Caillte. They were attempting to undo the damage of the forces of imperialism, feudalism, and Christianization that would later evolve and coalesce into what we now know as Capitalism and whiteness. They were attempting to retribalize themselves, to restore community government on democratic means, to restore their ancient faith, and to allow everyone the freedom to their own spiritual path. We need to learn from their mistakes and emulate their successes.

All power to the people, all glory to the Gods and Ancestors. Take care, comrades, or I suppose I should call you my stellinga.

Sources:

Goldberg, Eric J. “Popular Revolt, Dynastic Politics, and Aristocratic Factionalism in the Early Middle Ages: The Saxon Stellinga Reconsidered.” https://www.jstor.org/stable/2865267

Bede. “Ecclesiastical History of England” The Project Gutenberg EBook of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of England by Bede

Tacitus. “Germania” The Germany and the Agricola of Tacitus., by Tacitus (gutenberg.org)